After using Theano as my primary machine learning framework for the past year and a half, I decided it was time to give another framework a chance. The painful debugging process in Theano had already sucked away too many hours of my time, and I kept hearing all about the nice new features present in frameworks like Tensorflow and PyTorch. Having already used Tensorflow for some small things, I decided to try out PyTorch, for a couple reasons:

- Most obviously, I was intrigued by the imperative programming style and its implications for debugging. This is the main advertised feature of PyTorch, and, I have to say, it’s quite enticing. The days of waiting for my Theano function to compile, only to receive a cryptic error message could be over.

- Second, the imperative structure also seems to allow for more flexibility and avoids awkward abtractions like

scanin Theano and TF. Writing native Python loops over tensors seems like a luxury. - Third, it makes a lot of sense for reinforcement learning, which is what I am beginning to work on as a graduate student. When you’re training a model in an active environment, it is nice for the computation to happen when the lines are read by the interpreter. Sure, you can compile your graph and have a function that produces all the outputs and updates all the weights you need at each step, but it’s nice to have the added flexibility.

- Last, I just wanted to learn something different. The graph-based computation approach of Tensorflow was similar enough to Theano that the only advantages were the types of things you would expect from a software project with a team of Google engineers behind it (nicer API, good debugging features, Tensorboard, etc.).

I decided to implement Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs1 since it was something I had already implemented in Theano as part of a previous project (link), and, as such, it would provide a good testing ground to compare my experiences with the different frameworks. My implementation is available here.

Writing this code turned out to be remarkably easy, and I think PyTorch has won me over. There are some things that I find to be a little clunky such as the fact that you have to wrap all of your data, first in a Tensor and then into a Variable, if you want to do backprop; however, these little bits of apparent clunkiness also give me a level of control over things that I appreciate. For example, any time I want to transfer something to a GPU, I have to explicity call .cuda() on it. While annoying at first, I realized that I am more aware of the cost of data transfer from CPU to GPU and much more likely to write efficient code as a result. Overall, I have to say I’m definitely happy enough with my experience to switch over to PyTorch for my next project!

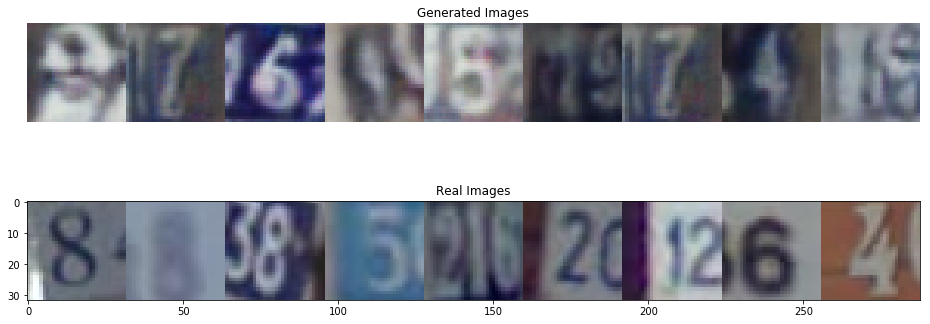

For my implementation of WGAP-GP, I deliberately chose to use a dataset that was not in the original paper, the Street View House Numbers dataset (SVHN). Though SVHN is not a particularly challenging dataset for generative modelling, I thought it would provide a mild test of the training stability that the authors claim (though, the experiments in the paper are quite thorough and convincing to begin with). Turns out, unsurprisingly, that the algorithm passed with flying colors. I got the below results on my first run, using the hyperparameters that the authors used for training on MNIST.

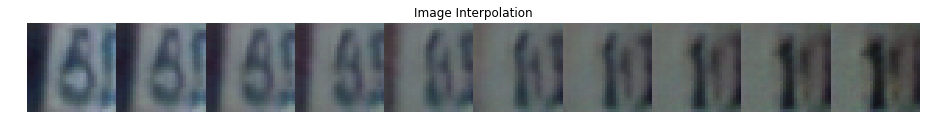

While, upon close inspection, it becomes clear which images are real and which are fake, this was impressive enough that I felt there was no need to even run it again. That may be a first in my ML career. You can also see the results of interpolating between two points in the noise space and feeding them through the generator network. These intermediate images form a smooth transition between the endpoints and show that the model is learning a meaningful latent space, rather than overfitting by memorizing the images in the training set. These positive results, achieved with minimal tedium, go to show that using a good framework to implement a good algorithm can go a long way in eliminating the headaches that are usually associated with Deep Learning training procedures.

-

Gulrajani, I., Ahmed, F., Arjovsky, M., Dumoulin, V., & Courville, A. (2017). Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.00028. ↩